Study Area

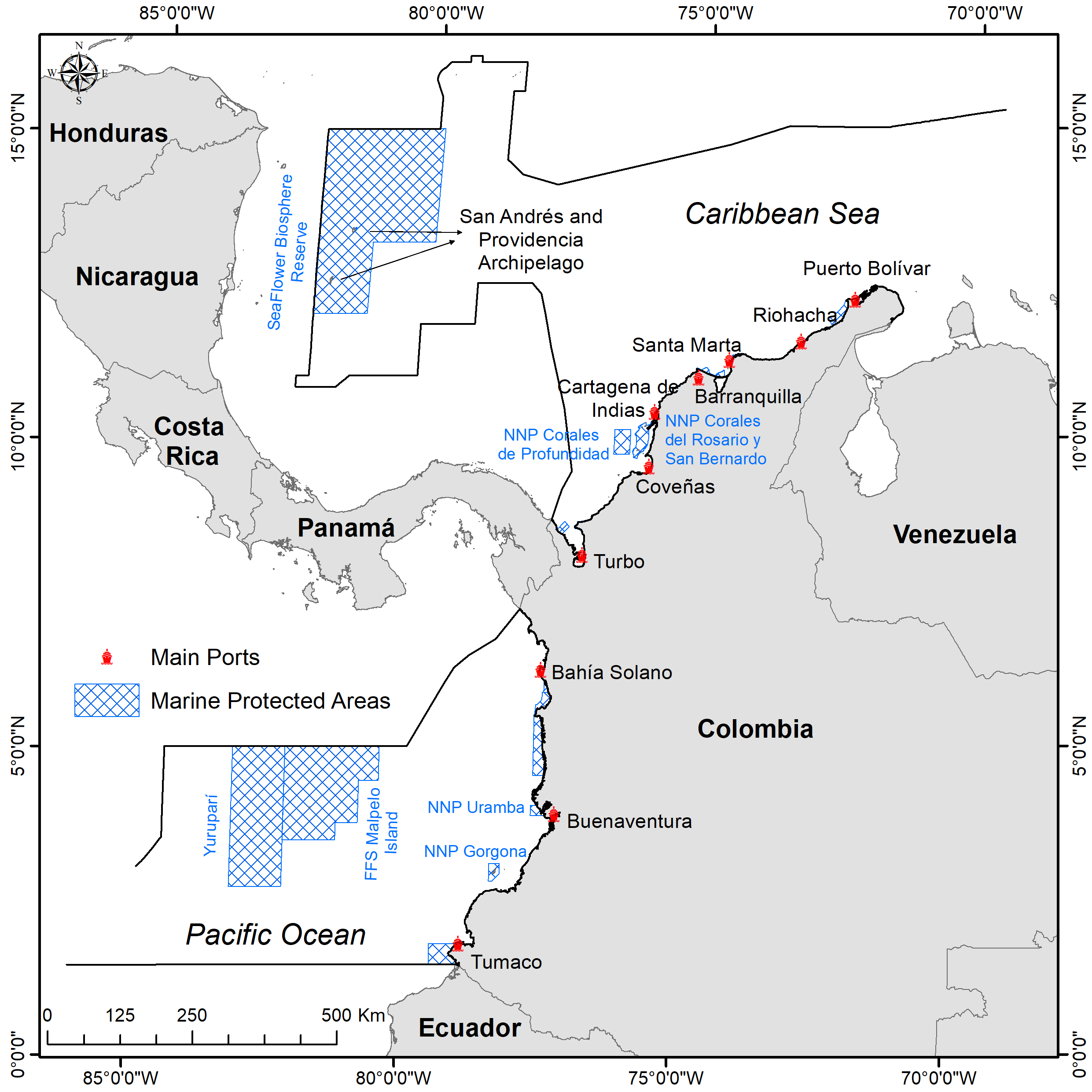

The Colombian state officially recognizes limits in the Caribbean Basin that enclose an area of approximately 589,302 \(km^2\), while the Pacific Basin covers an area of 332,129 \(km^2\). As of the present study, seven protected areas are recognized in the Caribbean Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) and six protected areas in the Pacific

Figure 1. Study area with the location of marine protected areas and main ports in the Colombian Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ).

The Colombian Caribbean is typically oligotrophic, except for some coastal regions such as Puerto Bolívar (La Guajira department) and Santa Marta (Magdalena department), where seasonal upwelling events increase coastal productivity, allowing for the presence of top predators such as cetaceans (Gordon 1967; Fajardo 1979; Andrade et al. 2003; Andrade and Barton 2005; Criales Hernández et al. 2006; Lonin et al. 2010; Paramo et al. 2011; Rueda-Roa and Muller-Karger 2013; Gutiérrez et al. 2015; Farías-Curtidor et al. 2017; Barragán-Barrera et al. 2019).). On the other hand, the Colombian Pacific is influenced by year-round coastal upwelling events, particularly during the months of February to April and November to December, as reported by Villegas (1997, 2003) and Díaz and Gusmao (2008). This leads to high productivity in coastal areas, particularly in the Gorgona Island National Natural Park (NNP) (Pineda 1995).

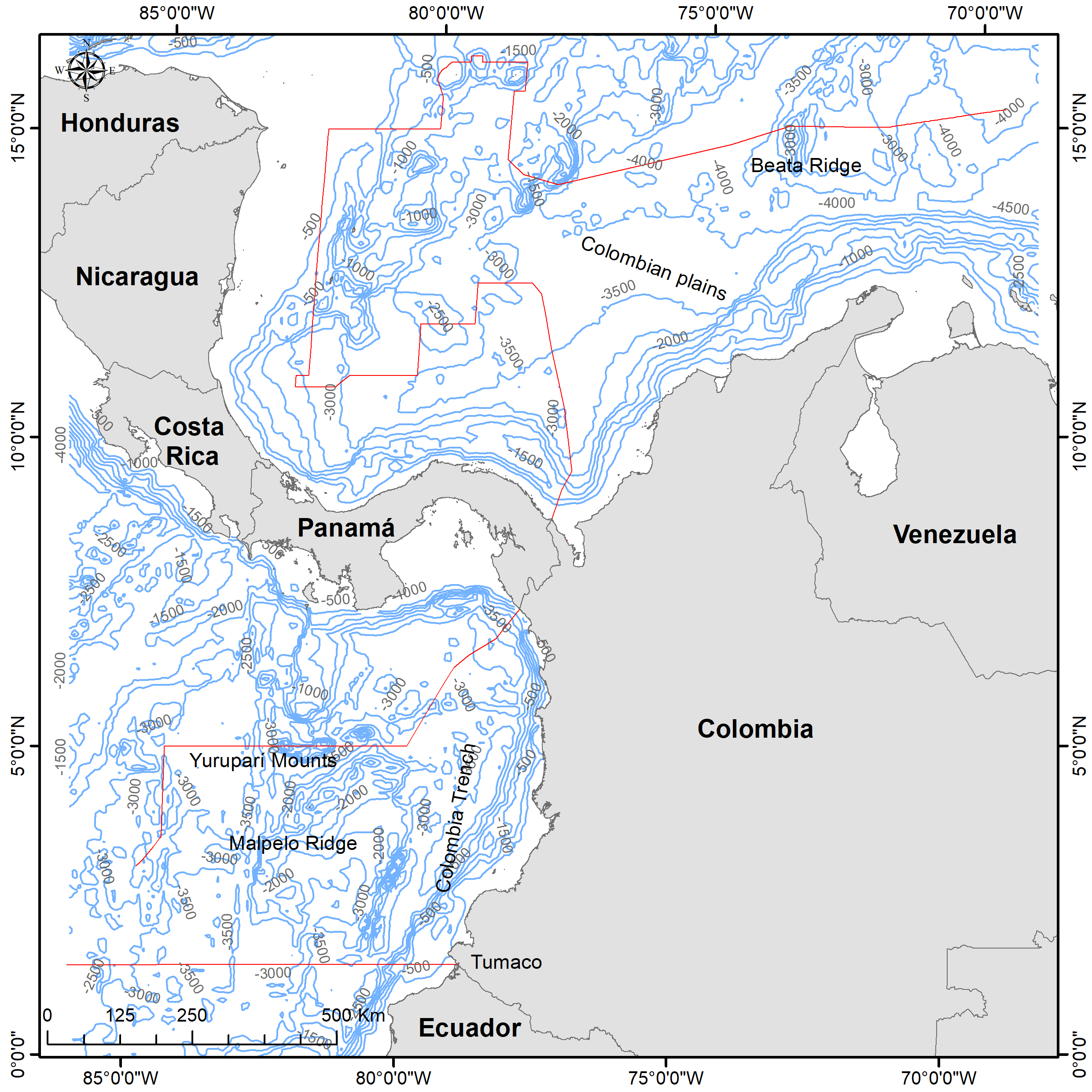

Figure S1. Contour lines of the bathymetry of the study area.

Both the Caribbean and Pacific areas in Colombia are influenced by tourism-related vessel activities. However, the main tourist attractions are different in each region. In the Caribbean, water tourism is focused mainly on cruise ships and diving activities, while in the Pacific, tourist vessel traffic is primarily for nature activities such as diving and whale-watching (Aguilera-Díaz et al. 2006; Sánchez and Jaramillo-Hurtado 2010; Brida et al. 2012; Trujillo and Ávila 2013 ). These differences are reflected in the tourist infrastructure, which is highly developed in the Colombian Caribbean with cities like Cartagena de Indias having a large hotel development (Aguilera-Díaz et al. 2006; Sánchez-Fernández et al. 2010; Brida et al. 2012). On the other hand, the Pacific region is more pristine and ecotourism and whale-watching activities are predominant, as the region is highly biodiverse and part of the breeding zone for stock G humpback whales (Flórez-González et al. 2007; Sánchez and Jaramillo-Hurtado 2010; Aguayo Lobo et al. 2011; Trujillo and Ávila 2013; Acevedo et al. 2017; Fagua and Ramsey 2019).